Could James II have avoided the Glorious Revolution if he had embraced a more moderate stance on religion? This question has intrigued historians for centuries, and it is one that warrants careful examination. A bold statement can be made: James II's reign was not doomed from the outset; rather, his unyielding commitment to Catholicism precipitated his downfall. His actions during his brief tenure as King of England, Scotland, and Ireland (1685–1688) highlight how personal convictions can shape political destinies.

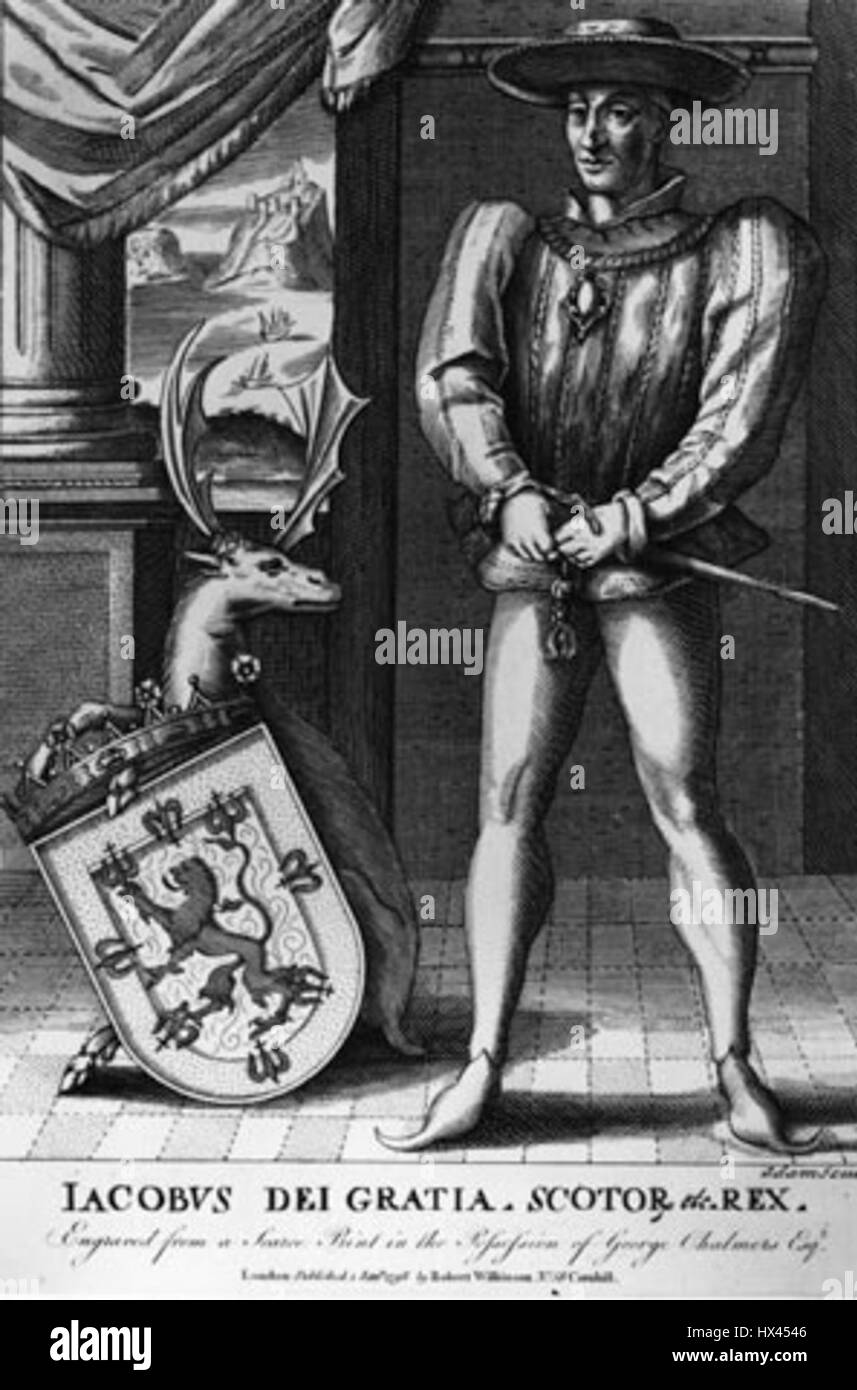

James Stuart, born on 14 October 1633 in Saint James’s Palace, London, was the second son of Charles I and Henrietta Maria. His early years were marked by the turbulence of the English Civil Wars, which erupted when he was just eight years old. By July 1646, Parliamentarian forces had confined him within the confines of his birthplace—a foreshadowing of the captivity that would define much of his later life. Following the execution of his father in 1649, James sought refuge abroad, returning only after the Restoration brought his brother Charles II to power in 1660. During this period, James distinguished himself as a naval commander, earning respect and admiration among his peers. However, his conversion to Roman Catholicism in 1670 set the stage for future controversy. When Charles II died without legitimate heirs in 1685, James ascended the throne, inheriting a kingdom deeply divided over religious issues.

| Bio Data | |

|---|---|

| Full Name: | James Stuart |

| Date of Birth: | 14 October 1633 |

| Place of Birth: | Saint James’s Palace, London |

| Death: | 16 September 1701 (aged 67) |

| Spouses: | Anne Hyde (m. 1660–1671); Mary of Modena (m. 1673–1701) |

| Children: | Mary II, Anne (both with Anne Hyde); James Francis Edward Stuart (with Mary of Modena) |

| Religion: | Roman Catholic |

| Reign: | 1685–1688 |

| Title(s): | Duke of York; King of England, Scotland, and Ireland |

| Notable Achievements: | Successful naval commander; introduced policies aimed at promoting religious tolerance |

| Legacy: | Deposed in the Glorious Revolution; last Roman Catholic monarch of England |

| Reference: | Royal Collection Trust |

James II's marriage to Mary of Modena in 1673 further inflamed tensions. The union between the widowed king and the devoutly Catholic princess from Modena symbolised his commitment to his faith, even as it alienated many Protestant subjects. Despite these challenges, James initially attempted to govern inclusively, issuing declarations of indulgence that granted greater freedoms to non-Anglicans. Yet such measures proved insufficient to quell opposition, particularly after the birth of a male heir, James Francis Edward Stuart, in 1688. This event triggered fears of an enduring Catholic dynasty, leading key figures in government—including members of James's own family—to invite William of Orange, stadtholder of the Dutch Republic and husband of James's Protestant daughter Mary, to intervene.

The subsequent Glorious Revolution saw James abandon his throne in December 1688, fleeing to France under the protection of Louis XIV. In exile, he continued to assert his claim to the crown, granting coats of arms to loyalists like Julien Campain, a Frenchman who sought recognition of his noble lineage through an elaborate genealogical document produced in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. This act underscores the symbolic importance James placed on maintaining connections to his former realm, even while living as a refugee.

Throughout his life, James demonstrated remarkable resilience and determination. From his early days navigating the treacherous waters of civil war to his later efforts to restore his authority, he remained steadfast in his beliefs. Nevertheless, his inability—or unwillingness—to compromise ultimately cost him his throne. As historian Wren noted, James might have succeeded in designing new structures for governance, but he failed to reconcile them with the prevailing sentiments of his people.

It is worth considering what might have happened had James adopted a different approach. If he had tempered his zeal for Catholic reform with pragmatic concessions to Protestant interests, could he have preserved his rule? Perhaps. Certainly, there were precedents for successful coexistence between competing religious factions in Europe. But James's legacy lies not in what might have been, but in what actually transpired: the establishment of parliamentary supremacy and the entrenchment of Protestant ascendancy in Britain.

In the aftermath of the revolution, James's daughters Mary II and Anne emerged as prominent figures in their own right. Both women inherited aspects of their father's complex character, balancing tradition with innovation. Their reigns reflected ongoing debates about monarchy, religion, and governance, themes that continue to resonate in contemporary discussions about constitutional democracy.

Examining James II's career offers valuable insights into the dynamics of leadership and resistance. His story illustrates how personal convictions can both inspire and undermine authority, shaping the course of history in profound ways. While some may view his deposition as inevitable, others see it as a cautionary tale about the dangers of inflexibility in the face of changing circumstances.

Ultimately, James II remains a fascinating figure whose impact extends far beyond the boundaries of his lifetime. Whether celebrated or condemned, his contributions to British history cannot be ignored. Through his actions—and perhaps more significantly, through his failures—he helped forge the modern nation-state, ensuring that future generations would grapple with questions of identity, sovereignty, and justice.