Is universal healthcare truly a fundamental right for every individual across the globe? A bold statement supporting this notion is that healthcare should not be a privilege but a basic human necessity. Brazil stands out as the only country where healthcare is free for everyone, enshrined in its constitution as a universal right. This principle forms the bedrock of equitable access to medical services, ensuring no citizen is denied essential care due to financial constraints.

The global landscape of healthcare systems varies significantly from one nation to another. While some countries offer comprehensive and universally accessible healthcare services, others lag behind, leaving their populations vulnerable to inadequate medical attention. In twenty-five European countries, universal health care operates through a government-regulated network of private insurance companies. These systems aim to provide coverage to all residents, regardless of their socio-economic status. However, the implementation and effectiveness of such schemes differ based on national policies and resources allocated towards public health infrastructure.

| Country | Healthcare System Type | Universal Coverage | Reference Website |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | Publicly funded single-payer system | Yes | Citizens International Blog |

| Norway | Taxpayer-funded national health service | Yes | Wikipedia |

| Germany | Mixed model with statutory health insurance | Yes | WHO Fact Sheet |

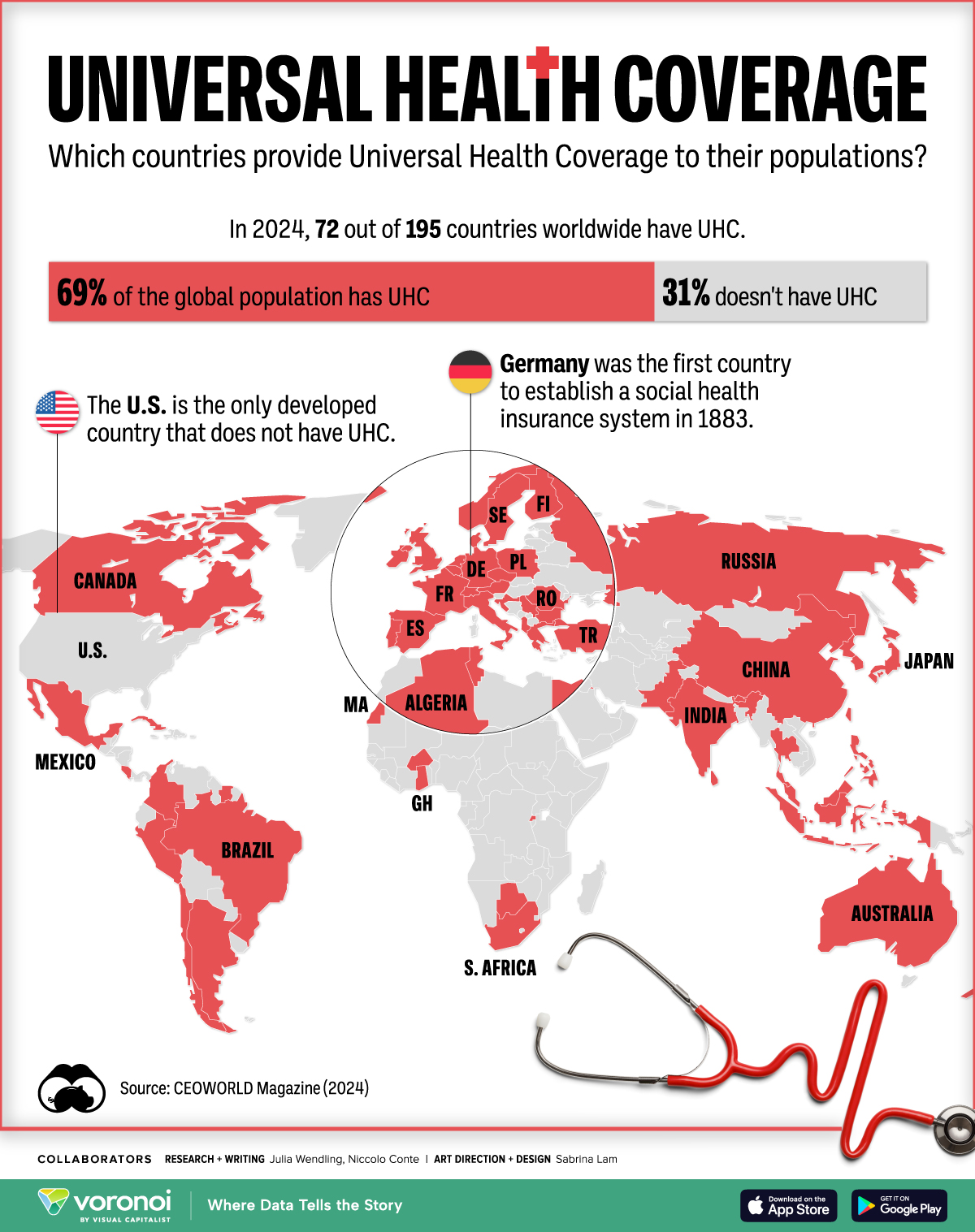

A map illustrating countries providing universal healthcare reveals an interesting pattern. Most nations depicted in green administer some form of universal healthcare plan. These plans are typically compulsory yet government-subsidized public programs designed to cater to the diverse medical needs of their populace. Notably, the United States remains almost entirely isolated among developed nations lacking universal healthcare coverage. This absence creates significant disparities in accessing affordable and quality medical treatments within its borders.

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) constitutes a critical target under Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It measures a country's capacity to guarantee that everyone receives necessary healthcare services whenever required, irrespective of geographical location or economic background. According to WHO fact sheets, UHC emphasizes safeguarding the most vulnerable segments of society by granting them unrestricted access to high-quality healthcare facilities without facing financial ruin. Implementing UHC empowers countries to maximize their greatest asset—human capital—by enabling individuals to lead healthier and more productive lives.

Among the top contenders offering free healthcare globally include Brazil, renowned for pioneering efforts in establishing a publicly funded single-payer system; Norway, which relies heavily on taxpayer contributions to sustain its robust national health service; and Germany, employing a mixed-model approach incorporating statutory health insurance mechanisms. Each of these nations demonstrates distinct approaches tailored specifically to address unique challenges posed by their respective demographics and resource availability.

For expatriates and international employees seeking second citizenship opportunities abroad, understanding potential healthcare benefits becomes paramount. Countries like those mentioned earlier present attractive options due to their commitment towards delivering inclusive healthcare solutions. Such provisions extend beyond mere treatment accessibility; they encompass preventive care measures aimed at enhancing overall well-being standards across communities.

An overview of countries offering free healthcare highlights intriguing insights into how different regions manage their public health responsibilities. With over 150 nations worldwide embracing various forms of universal healthcare frameworks, it underscores a growing consensus regarding the importance of prioritizing population health management strategies. Nevertheless, certain gaps persist concerning uniformity in service delivery levels between urban versus rural areas alongside inequities experienced by marginalized groups who might still encounter barriers despite existing legal protections.

In conclusion, while progress continues toward achieving universal healthcare goals globally, ongoing efforts must focus on addressing persistent issues affecting equitable distribution of resources and eliminating residual inequalities hindering full realization of this vital objective. By learning from successful models implemented elsewhere, policymakers can devise innovative ways to enhance domestic healthcare capacities ensuring broader inclusivity moving forward into future decades ahead.